According to Wingchi Ip (on the left hand side), tea can be viewed as an expression of the Dao. A path he has been following for over thirty years, amidst his personal collection of Yixing teapots, his education in ceramic arts and economics and his occupation as a professor, followed by his tea business and Lockcha, the tea house chain he founded in Hong Kong in 1991.

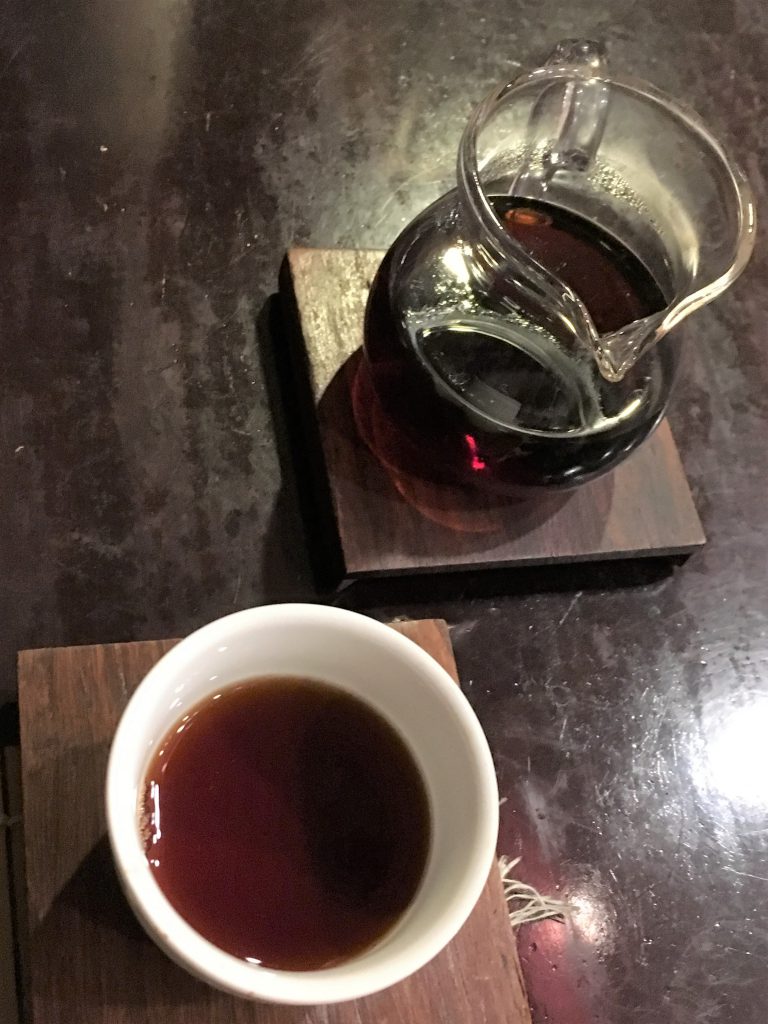

Over the last fifteen years, he has been organizing classical Chinese music concerts at his Lockcha’s shop in Admiralty. Before the show begins, whilst welcoming guests and friends, we had a chat around a cup of pu’er tea.

Thank you for this cup of pu’er. What tea are you having?

Mine is also a pu’er. Its color is darker than yours but the taste is very mellow. It’s very good for health, especially after reaching a certain age. This is my daily tea. It is similar to yours (editor’s note: mine has a classic orange robe) but darker because it has been brewed for a longer time and with more tea leaves. That’s why you get something different.

How different?

I think for tea people, tea is a training of your rational thinking. We study so many details, the aroma, the taste, etc. It is a kind of practice I think, that helps you understand what you are really doing, eating and drinking.

This is very important in modern days. We eat but some people do not really know what they are eating. It’s not only a matter of whether such or such food is organic or not.

There is a common saying according to which ‘you are what you eat’. Why would you choose to eat or drink this or that? What is the after taste of a particular tea? This teaches us to pay attention to details.

In a certain way, it’s a matter of being mindful to what is surrounding us. Would you say this goes hand in hand with a renewed interest for tea in general?

You could say so. Drinking tea has become a practice of the mind. In older times, we paid more attention to what we were absorbing. When you don’t have the knowledge, you have to find out what you can and cannot eat, or else you die. In the past, people had to be very careful and explore thoroughly. Now the knowledge is in abundance but it is not really verified knowledge.

People are given lots of recommendation but don’t really understand them. In the food world, it has always been this way. One day, someone might say, animal fat is not good, so I prefer vegetables. Then, we’ve had margarine. The day we learn that this hydrogenated oil is a cause of some cardio vascular diseases, we shift to olive oil. But we don’t really understand why, in reality.

Yet, what matters is to find a proper way for our own life, instead of thinking in terms of what is good or not because we are surrounded by so many things that are not doing us any good at some point. Instead of following what we are being told, we can open our mind, release some stress, put down all our preconceptions, focus on what our body is telling us on which is good and not good… for us. By opening up our heart to nature, we can find out how to have a balanced life. Call it mindfulness, wellness or else.

This is more life wisdom than knowledge, if you will. Actually, it relates to this idea in Buddhism that you just have to go back to your own heart. Your heart can feel, your heart can know, can understand what is good for you, as well as the true meaning of your life.

What’s new for you, at the moment?

At the moment, I’m studying Japanese green tea. With the famous tea company Koyamaen (editor’s note: which manufactures tea since the 17th century in Uji), which supplies most Japanese tea ceremony schools such as Urasenke, we are working on crafting a tea for my teahouse.

I have to choose carefully a tea that is suitable for the Chinese palate. It would be the first time that they create a tea specifically for a Chinese tea house. For me, it is a great honor.

The teas from Koyamaen originate from Uji and I particularly appreciate the teas of this region. They come as a bit mellow, not too fragrant but with a very fine texture and body. I’m mostly choosing teas with amino taste.

At the moment, I have to understand the distinctive features of Japanese teas according to their origin, the methods of preparation… I approach this from the perspective of the Chinese consumers’ palate. Chinese tea drinkers can take a little bit of bitterness but not too much of astringency. Astringency relates to the sweet aftertaste in the mouth and has to remain light in order to easily shift to another taste.

How about umami?

Chinese tea drinkers quite like the umami taste. Some high quality and premium teas, such as Longjing (龍井) or Bi Lo Chun (碧螺春) or the very soft tips of certain tea trees, also possess this taste. Japanese tea manufacturers sometimes use specific techniques to accentuate the umami flavor. In Japan, I have tasted a lot of sencha, gyokuro. Each region has a unique flavor. Those of Sika, Uji near Kyoto are my favorites.

What are some of the noticeable evolutions that you have recently observed in the processing of tea?

There are so many. Just to pick one, there are many novel methods of tea processing with varietals and crossovers that outdate what we usually read about the 6 categories of tea (editor’s note: white, yellow, green, oolong, black, pu’er). As an example, it is not uncommon now that black tea sometimes gets roasted or baked in order to accentuate the aroma.

Technology now supports the experiment of hybrids and offers more stability, whereas in the past, it was only possible to get the seed and this left ample room for variations in the tea leaves’ growth and taste. Now, different genes get mixed together.

The genetics of tea is easy to change and modify so it’s easy to conduct some experiments, sometimes in labs, sometimes naturally. In Japan, they do that a lot. Since everyone is now looking for free green tea, hybrids allow to innovate. That’s how Taiwanese tea #12, Jing Xuan (金萱) which is recognizable by its milk aroma, has come to life.

Does any of these teas taste good, in your opinion?

Not really at this point in time, I would say.

For instance, the Four Seasons of Spring in Taiwan (Si Ji Chun, 四季春) can grow throughout the year in high yields but the taste lacks character and the fragrance is very common. By contrast, the Wuyi Rock tea (武夷岩茶) is very tasty but there is only one crop per year, it is therefore more expensive.

Some hybrids are interesting productivity-wise but not necessarily in terms of taste, aroma, and for the tea tree. It is challenging to create a tea that meets the farmers requirements in terms of yield, and fulfill the expectations of tea connoisseurs at the same time.

How do you view these experimentations?

I think it’s good because it opens up new possibilities, allows to explore how to get better products, and this is totally fine as long as they only mix tea genes. I do hope they will maintain some traditional single origin teas, though!

Mono-culture usually ends up in disasters. Diversity is needed. Just like in the realm of ideas, if we end up with only one unique way of thinking, things can get dangerous. This is simple wisdom of life.

When you hold a gongfucha gathering with friends, what matters the most to you, between the tea, the tea ware, etc.?

You can consider this at three different levels.

Firstly, you have the tea, its fragrance, its aroma, its intrinsic quality in terms of ‘is it a good tea or not’.

Secondly, you have the tea ware, which is more visible and tangible than the taste, and the aroma.

Finally, you have the preparation, the ceremony itself, your gestures, how you present it. It can follow a particularly slow pace, like in Japanese chanoyu. In some cases, the ritual, the calmness, the peacefulness, the serenity one can feel during the gathering will be more important than the tea itself.

In Chinese culture, the principle of the Dao is extremely abstract. “The Dao that can be expressed in words is not the lasting Dao.” (道可道 非常道) is the first sentence of the Laozi.

To reach the Dao, we rely on elements as practical as tea, the tea ware and the ceremony, which each individually conveys specific meanings. All these messages are not the Dao itself but an expression of it.

The tea is partly abstract. The tea ware is the most tangible element. The ceremony is completely ritual. Each time you hold a tea preparation, these three elements vary in importance according to the situation. In a certain way, they form the Trinity of tea, if you will!

Could you describe the very first teapot of your collection? What meaning did it have for you?

It was in 1969. I was in middle-school. It was a very small teapot, a very cute one. I was attracted by the different forms and sizes of teapots. For me, it was no more than a toy! But through such objects, I learned to appreciate their variety and craftmanship.

I developed a sort of relationship with these objects which remind me of a manual intervention, of something that is deeply humane. Over time, I realized that my passion for these teapots transpired something that was coming from my heart and my soul. I was in awe with such objects which were very far from my preoccupations as a secondary school student in Hong Kong.

It was a Shuiping teapot, a very common one. At that time, there were only 30-ish or 40-ish shapes that could be found. I started to appreciate these teapots without any prior knowledge, by just following my personal inclinations for miniatures. Looking back, I realize this has affected the rest of my life.

Do you have the sensation that technologies, such as 3D printing, will affect craftsmanship in teaware?

Life is all about diversity which makes it more interesting, less boring. For me, whatever technological progress we go through, the pleasure and satisfaction that derives from the appreciation of craftsmanship will live on.

Technology makes our lives more comfortable, allows us to experiment new forms of entertainment but this is very ephemeral. As human beings, we do not change that much. We go through joy and sorrow, we aspire to a minimum of security and respect… This has always been since the dawn of time.

For this reason, I do not think the joy that exudes from craftmanship can be replaced by anything else as long as we remain deeply and profoundly true to our human nature.

Key Dates

1977. Graduated in Economics, New Asia College (Hong Kong)

1978. Graduated in Fine Arts, New Asia College (Hong Kong)

1991. Foundation of LockCha

2003. Opening of LockCha shop in Admiralty (Hong Kong Park)

See also

This interview in French. Hong Kong | Un pu’er avec Wingchi Ip

Yumcha au LockCha Tea House (in French)

Interview conducted in Hong Kong on June 2, 2019.